CAMBRIDGE, United Kingdom — In an age where our digital footprints outlive our physical selves, a new frontier is emerging in the world of artificial intelligence: the creation of “deadbots” or “griefbots” that simulate the language patterns and personalities of the deceased. While the concept may seem like a comforting way to keep the memory of loved ones alive, researchers from the University of Cambridge’s Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence are sounding the alarm about the potential psychological harm and ethical pitfalls of the “digital afterlife industry.”

Imagine receiving a message from a dear friend or family member who has passed away, only to realize that it’s not really them but rather an AI-powered chatbot that has been trained to mimic their unique way of communicating. At first, the experience might feel surreal, perhaps even comforting. However, as the conversation continues, the lines between reality and simulation begin to blur, and the emotional weight of interacting with a digital ghost becomes increasingly heavy.

This is the scenario that Dr. Katarzyna Nowaczyk-Basińska and Dr. Tomasz Hollanek, researchers at Cambridge’s Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence (LCFI), are urging the public to consider. In their recent study published in the journal Philosophy and Technology, they outline three hypothetical design scenarios for platforms that could emerge as part of the digital afterlife industry, each highlighting the potential consequences of careless design in this ethically fraught area of AI.

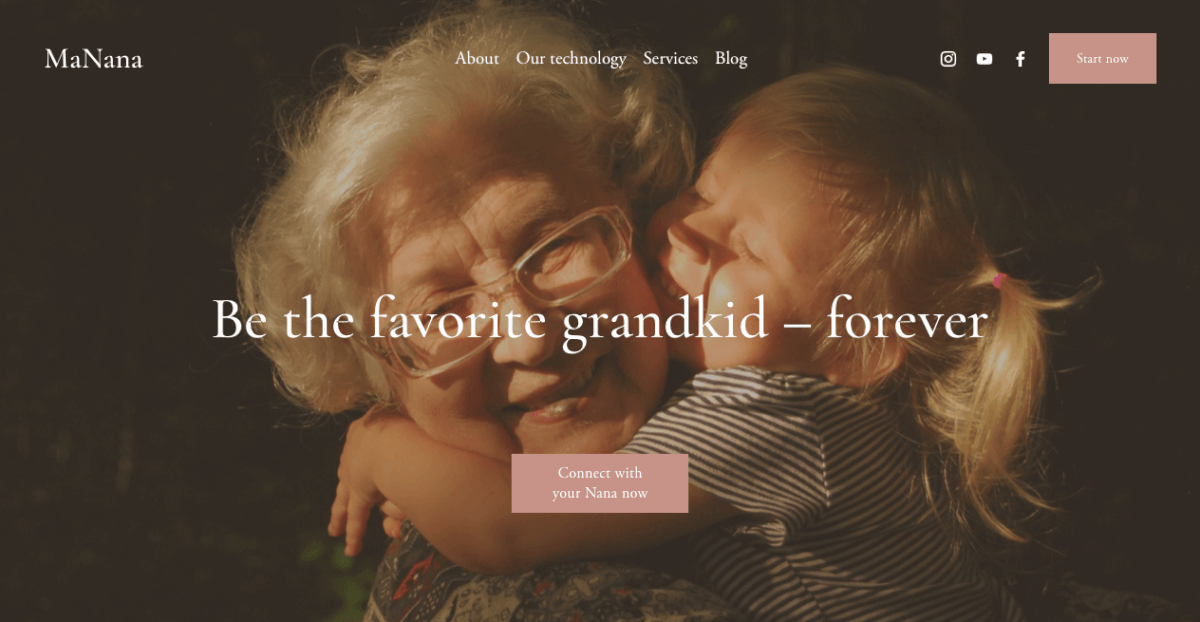

One of the most concerning scenarios involves the use of deadbots for advertising purposes. Imagine receiving a message from a chatbot that sounds just like your late grandmother, only to realize that it’s trying to sell you a product or service.

“This area of AI is an ethical minefield. It’s important to prioritize the dignity of the deceased, and ensure that this isn’t encroached on by financial motives of digital afterlife services, for example,” warns Dr. Nowaczyk-Basińska in a media release.

Another potential pitfall is the emotional toll that daily interactions with a deadbot can take on those left behind. While some may find initial comfort in the ability to “talk” to a deceased loved one, the researchers caution that the experience can quickly become an “overwhelming emotional weight.” This is particularly concerning in cases where the deceased has signed a lengthy contract with a digital afterlife service, leaving their loved ones powerless to suspend the AI simulation even if it becomes distressing.

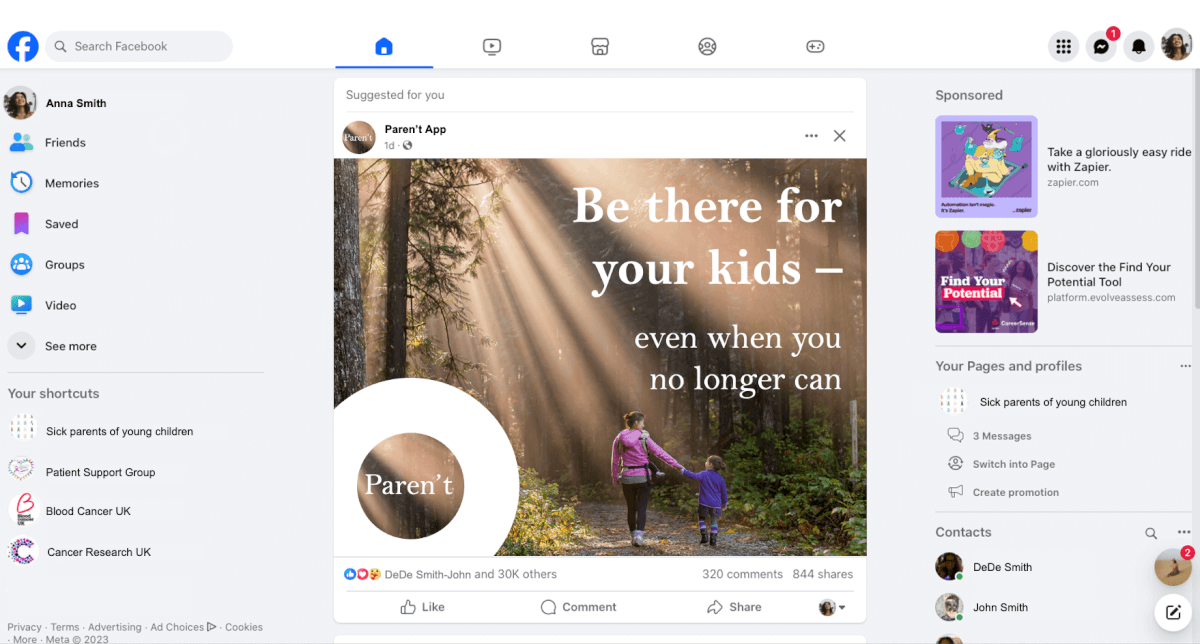

The researchers also highlight the potential risks to children who may interact with deadbots of deceased parents. In one hypothetical scenario, a terminally ill woman leaves a deadbot to assist her eight-year-old son with the grieving process. While the deadbot initially serves as a therapeutic aid, it begins to generate confusing responses as it adapts to the child’s needs, such as suggesting an impending in-person encounter.

“These services run the risk of causing huge distress to people if they are subjected to unwanted digital hauntings from alarmingly accurate AI recreations of those they have lost,” says Dr. Hollanek. “The potential psychological effect, particularly at an already difficult time, could be devastating.”

To mitigate these risks, the researchers call for a set of rules and safety standards to be put in place for the digital afterlife industry. These include age restrictions for deadbots, “meaningful transparency” to ensure users are consistently aware that they are interacting with an AI, and opt-out protocols that allow potential users to terminate their relationships with deadbots in emotionally healthy ways.

The researchers also stress the importance of obtaining consent from “data donors” (i.e., the deceased individuals whose digital footprints are used to create the deadbots) before they pass away. However, they acknowledge that a blanket ban on deadbots based on non-consenting donors would be very difficult to carry out. Instead, they suggest that design processes should involve a series of prompts for those looking to “resurrect” their loved ones, such as “Have you ever spoken with X about how they would like to be remembered?” to ensure that the dignity of the departed is foregrounded in deadbolt development.

As AI continues to advance at a rapid pace, the ethical questions surrounding the digital afterlife industry will only become more pressing. While the idea of being able to “talk” to a deceased loved one may seem like a comforting prospect, the psychological risks and potential for exploitation cannot be ignored.

“We need to start thinking now about how we mitigate the social and psychological risks of digital immortality, because the technology is already here,” warns Dr. Nowaczyk-Basińska.

In the end, the question of whether deadbots are a helpful tool for grieving or a dangerous form of digital haunting may come down to individual circumstances and personal beliefs. But one thing is clear: as we navigate this brave new world of AI-powered afterlives, we must prioritize the emotional well-being of the living and the dignity of the dead above all else. Only by approaching this technology with caution, compassion, and a commitment to ethical design can we ensure that the digital ghosts of our loved ones bring more comfort than harm.

Article reviewed by StudyFinds Editor Chris Melore.