HEXHAM, United Kingdom — Vindolanda served as an ancient Roman auxiliary fort in the north of what is now the United Kingdom for nearly 300 years (roughly 85 AD -370 AD). Now, a new analysis has identified what looks to be the first ever known example of a disembodied phallus made of wood recovered anywhere in the Ancient Roman world.

Phalli were actually quite ubiquitous at the time across the Roman Empire, as they were believed to help promote good luck and ward off bad fortune. People would wear necklaces featuring phallic pendants, and phallic images were often seen in painted frescoes and mosaics. They even formed part of the decoration of other objects such as knife handles or pottery.

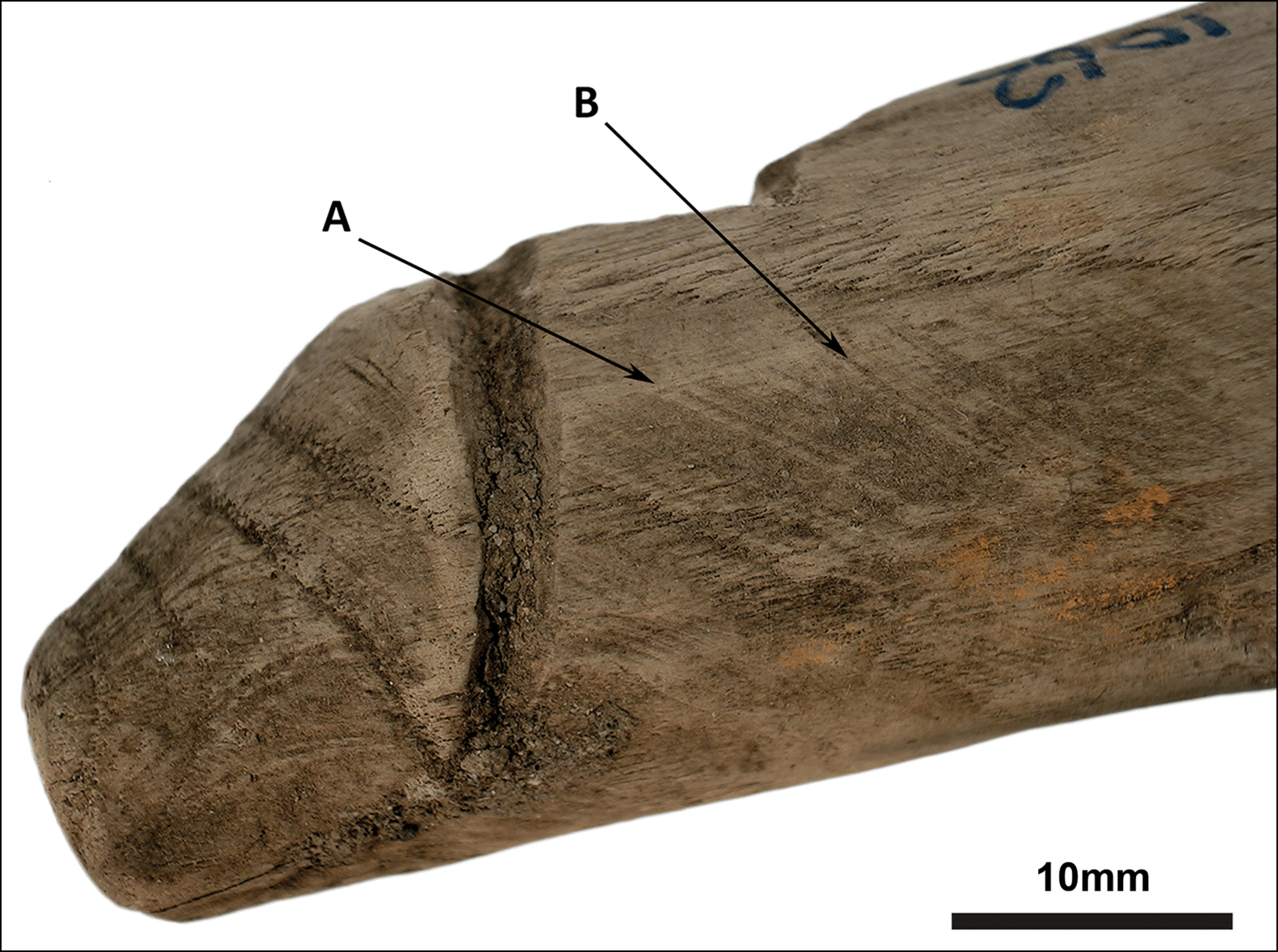

The particular wooden phallus analyzed by researchers at Newcastle University and University College Dublin, however, may have served a decidedly more sensual role. Study authors’ analysis revealed that both ends of the phallus, first discovered at Vindolanda in 1992, were noticeably smoother, which is indicative of repeated contact over time.

“The size of the phallus and the fact that it was carved from wood raises a number of questions to its use in antiquity. We cannot be certain of its intended use, in contrast to most other phallic objects that make symbolic use of that shape for a clear function, like a good luck charm. We know that the ancient Romans and Greeks used sexual implements – this object from Vindolanda could be an example of one,” says Dr. Rob Collins, Senior Lecturer, Archaeology, Newcastle University, in a statement.

The research team explored three possible explanations regarding the phallus’ true purpose. The first theory is that it was used as a “sexual implement,” it is life-sized after all. The second possible explanation is that the object was used as a pestle, either in kitchens or to grind ingredients for cosmetic or medicinal purposes. Its size would have made it easy to handle, and its shape would have “granted” the food or ingredients being prepared with perceived magical properties.

The last theory is that the phallus had been attached to a statue which passers-by would touch for good luck or to absorb or activate protection from misfortune. As surreal as all that sounds, this was a common practice throughout the Roman empire. If this theory is true, the statue was probably located close to the entrance of an important building such as a commanding officer’s house or a headquarters of some kind.

The evidence we do have, though, indicates the object was probably either indoors, or at the very least, not in an exposed position outside, for a very long time.

“Wooden objects would have been commonplace in the ancient world, but only survive in very particular conditions – in northern Europe normally in dark, damp, and oxygen free deposits. So, the Vindolanda phallus is an extremely rare survival. It survived for nearly 2000 years to be recovered by the Vindolanda Trust because preservation conditions have so far remained stable. However, climate change and altering water tables mean that the survival of objects like this are under ever increasing threat,” explains Dr. Rob Sands, Lecturer in Archaeology, University College Dublin.

“This rediscovery shows the real legacy value of having such an incredible collection of material from one site and being able to reassess that material. The wooden phallus may well be currently unique in its survival from this time, but it is unlikely to have been the only one of its kind used at the site, along the frontier, or indeed in Roman Britain,” concludes Barbara Birley, Curator at the Vindolanda Trust.

For anyone interested in taking a closer look, the phallus is now on display at the Vindolanda museum.

The study is published in Antiquity.

Awww, quit dickin’ around. Tell us what it was REALLY used for.

😆😆😆😆