Article written by Bill Sullivan, Indiana University

Imagine you’re a police officer. You spot a car that’s swerving all over the road. You pull the driver over, and they’re clearly intoxicated. With slurred speech, they swear that they haven’t had a drop of alcohol all day. Would you believe them?

In 2024, a Belgian man was acquitted after he was cited three times for DUI within four years. Though his job at a brewery likely raised suspicions, he insisted that he hadn’t been drinking. Three doctors confirmed that he suffered from a condition called auto-brewery syndrome and was unaware. People with this syndrome carry microbes in their intestines that produce abnormally high levels of alcohol when breaking down sugars and carbohydrates.

Though it’s a rare condition, a woman was acquitted of her DUI charge in 2016 after doctors diagnosed her with the same syndrome. She had a blood alcohol level four times the legal limit.

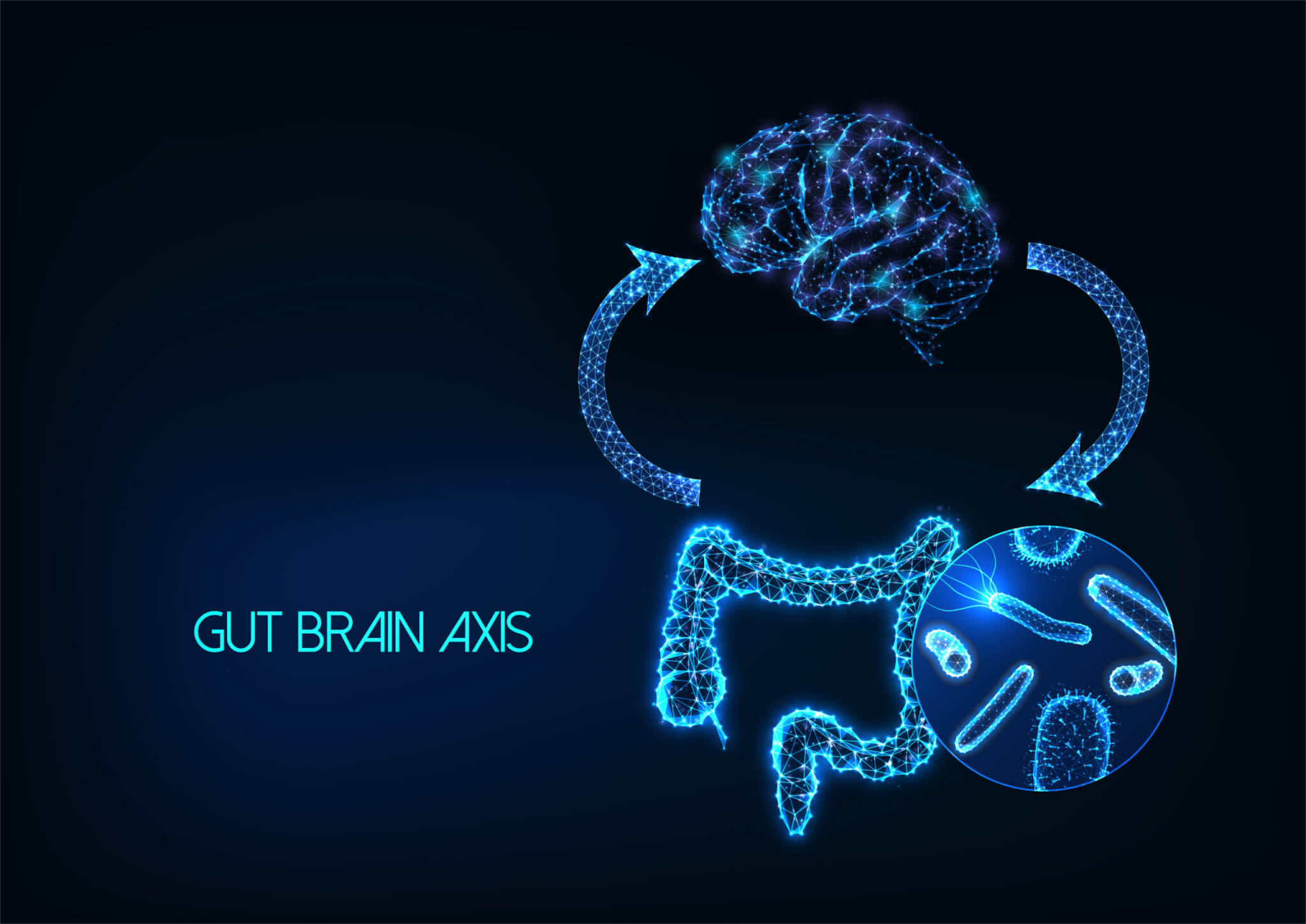

I am a microbiologist who is intrigued by the roles the gut microbiome plays in human health. As the author of the book “Pleased to Meet Me: Genes, Germs, and the Curious Forces That Make Us Who We Are,” I have done extensive research into how your microbiome affects your health, mood, and behavior. It turns out the specific species of bacteria in your intestines at the root of auto-brewery syndrome may also cause fatty liver disease by producing high levels of alcohol.

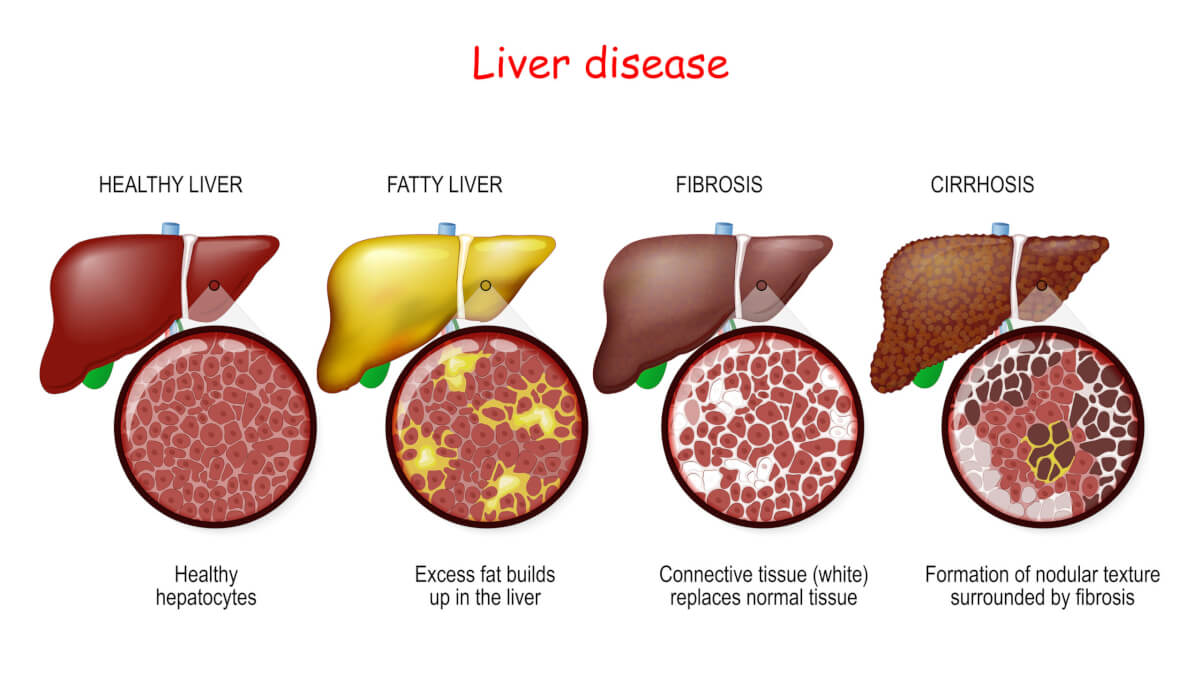

Diseased liver, without drinking

The accumulation of excess fats in the liver can cause serious health problems, including inflammation. This can lead to cirrhosis, or scarring, and liver cancer. Most people associate fatty liver disease with alcoholism. However, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, or MASLD, arises without excessive alcohol intake. Formerly known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, this condition affects 80 million to 100 million Americans.

There appear to be multiple causes of MASLD, such as obesity, insulin resistance, high cholesterol and hepatitis C infection. Microbes may be another.

In a 2019 study, physicians identified a patient who was suffering from both auto-brewery syndrome and severe MASLD. When researchers examined stool samples from the patient, they found a species of bacteria called Klebsiella pneumoniae. This particular strain of K. pneumoniae was making between four and six times the quantity of alcohol that strains of the same bacteria make in healthy people. Examining a cohort of 43 other patients with MASLD, they discovered that 61% of participants possessed K. pneumoniae excreting unusually high amounts of alcohol. Among the 48 healthy people included as controls, only 6% had such bacteria.

The team noted that K. pneumoniae bacteria was only slightly more abundant in the intestines of MASLD patients. It was the quantity of alcohol that the microbes produced that differed. But could the excessive alcohol the bacteria was making actually give rise to fatty liver?

A microbrewery in the gut

To understand whether microbes were really to blame for fatty liver, the scientists fed the high-alcohol-producing K. pneumoniae bacteria to healthy mice. Within one month, these mice developed measurable symptoms of fatty liver, which progressed to cirrhosis within two months. The bacteria-triggered liver disease followed the same timeline the researchers observed when they fed the mice pure alcohol.

Further supporting their hypothesis, transferring intestinal material from either mice or humans with MASLD into healthy mice led them to develop fatty liver damage.

Finally, researchers treated the intestinal material harvested from MASLD mice with a virus that kills only Klebsiella. When intestinal material free of Klebsiella was transplanted into healthy mice, they didn’t develop any disease.

Their results suggest that certain K. pneumoniae bacteria make excessive alcohol that can lead to fatty liver. This also means that some K. pneumoniae-induced cases of fatty liver might be treatable with antibiotics. Indeed, giving the antibiotic imipenem to mice with K. pneumoniae-induced fatty liver reversed progression of the disease.

Since K. pneumoniae converts sugar to alcohol, physicians may be able to diagnose this form of fatty liver with a simple blood test to measure blood alcohol levels in response to sugar. The researchers showed that mice harboring the alcohol-producing Klebsiella bacteria became inebriated and showed increased blood alcohol levels after consuming sugar.

It isn’t clear whether this phenomenon is widespread. Klebsiella bacteria is commonly found in human intestines, but it is unknown why some people harbor strains that make high levels of alcohol.

In the bigger picture, the study further illustrates the importance of the microbiome in regulating mood and behavior. Some people may possess intestinal microbes secreting enough alcohol to make them act drunk when, in fact, they ate only a sweet dessert, as was the case with the woman charged with DUI. The Belgian man is also trying to minimize the amount of alcohol his gut microbes make through dieting and medication. Whether these people have a greater tolerance for alcohol through constant exposure is another question.

This article, originally published Sep. 30, 2019, has been updated to include details from a 2024 DUI case.

Bill Sullivan is a professor of Pharmacology and Toxicology at Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()