Written by Philip C. Almond, The University of Queensland

New norms for differentiating supernatural phenomena from the natural within Roman Catholicism took effect on May 19. The new norms arise from the need to evaluate as quickly as possible the supernatural origin or otherwise of an array of phenomena occurring increasingly within the Catholic world and spreading quickly via social media.

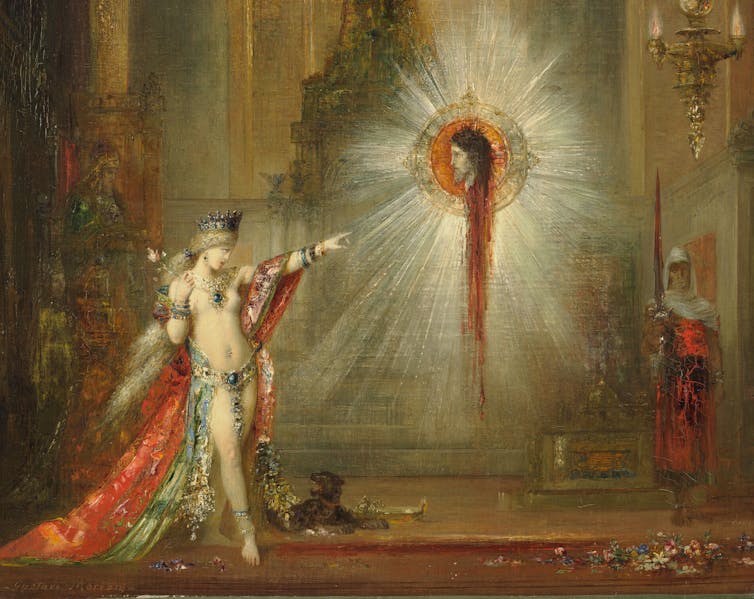

Possible supernatural phenomena include apparitions – especially of Jesus or the Virgin Mary – interior or exterior voices, writings or messages from the beyond, the weeping or bleeding of sacred images, the bleeding of consecrated eucharistic hosts, and so on. Visions of the Virgin Mary, in particular, continue to occur regularly within Catholic Christendom.

The new document neither endorses supernatural phenomena nor rejects them. Rather, it provides a set of criteria and processes by means of which the church can officially discriminate between them and separate the authentic from the fake.

So what do we need to know about these norms?

An old document replaced

The new norms replace an earlier document from 1978.

In this 1978 document, the decision whether to approve a phenomenon as supernatural or not was essentially left in the hands of a local authority – in most cases, a diocesan bishop.

According to criteria, the bishop decided on a choice of two options: supernatural, or not.

In the case of a judgment that a phenomenon was of supernatural origin, he could permit a public manifestation of devotion to the supernatural phenomenon equivalent to his saying, “for now, nothing stands in the way” (“pro nunc nihil obstat”).

Under this document, central control of the Vatican was minimal. Local authorities were in control.

The supernatural is under new management

The new document is intended to more effectively oversee the validation of such events.

It does so by centralizing authorization, management, and control of the supernatural within the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, better known as “the Inquisition.” Any decision bishops or any other authority wish to make has to be submitted to the Dicastery for approval.

The new document declares the Holy Spirit may “reach our hearts through certain supernatural occurrences such as apparitions or visions of Christ or the Blessed Virgin.”

But the central authority of the church will now decide where, when and how God works, His wonders or miracles to perform.

Overall, God will be shown to be minimally directly intervening in the world.

Six new criteria to judge whether God is involved

Rather than a relatively simple judgment whether an event is supernatural or not, the church now provides six possible ways an event can be classified. These range from “nihil obstat” (“nothing stands in the way”) to “declaratio de non supernaturalitate” (“declaration of non-supernaturality”).

But even where a nihil obstat is granted, as a rule, neither a diocesan bishop, nor any conference of bishops, nor the Dicastery itself “will declare that these phenomena are of supernatural origin.”

In short, a clear declaration of a supernatural event having taken place will virtually never happen (or, at least, unless the Pope intervenes).

A declaration of non-supernaturality will be made if it is discovered “the phenomenon was based on fabrication, on an erroneous intention, or on mythomania.”

In short, if a fake or a hoax is discovered.

Between these two extremes lie four other possible judgments. Although there are positive signs of divine action in each of these, they each indicate increasing worries about credibility. The first two of these concern increasing doubts about the credibility of the phenomenon. The next two concern increasing doubts about the honesty of the people involved.

What are the new procedures?

If a diocesan bishop, after consultation, believes a supernatural phenomenon requires investigation, he alerts the Dicastery.

He then convenes an Investigatory Commission to carry out a “trial.” This trial will see witness examinations, sworn depositions, expert analysis of written texts, along with technical-scientific, doctrinal and canonical assessments. It is pretty much the traditional method of the Inquisition in modern dress (or vestments).

The commission finally makes a judgment on the truth of the matter based on positive and negative criteria.

Positive criteria include the reputation of persons involved, doctrinal orthodoxy, exclusion of fakery and the fruits of Christian life that have resulted from it.

Negative criteria include the possibility of manifest error, potential doctrinal errors, breeding of division within the church, an overt pursuit of profit, power, fame or social recognition, and the personal and public ethical rectitude of those involved, along with their mental health.

In the light of the commission’s work, the bishop proposes to the Dicastery a judgment following one of the six ways of classification. The Dicastery then makes a final judgment to be delivered to the bishop, who is obliged to implement the decision and make it public

Catholicism ‘disenchanting’ the world

There is deep concern within the Vatican over misinformation and disinformation about the supernatural.

The document informs us: “Now more than ever, these phenomena involve many people […] and spread rapidly across different regions and many countries.”

The digital world is a place of multiple meanings where the supernatural occupies a space somewhere between reality and unreality. It is a domain where belief is a matter of choice and disbelief is willingly and happily suspended.

Ironically, the outcome of the new norms will be to minimize the number of phenomena recognized as “supernatural” within the Catholic Church. In effect, it will put stricter limits on God’s action within the world.

The new norms within the church to manage the supernatural are intended more to “disenchant” the world than further to “enchant” it.

Philip C. Almond is an Emeritus Professor in the History of Religious Thought at The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.